1. Context and objectives of emulation in serial communication

The development of devices and applications connected via a serial link is typically divided among multiple teams and runs in parallel. In practice, this means that one side of the interface is often unavailable, incomplete, or unstable at certain stages of the project. Emulation supplements the missing communication counterpart so that development and testing can continue without waiting for physical hardware or final protocol implementation.

Emulation has two basic directions in serial communication:

- Device emulation: the terminal acts as a sensor/control unit and provides the data flow and responses expected by the application under development. The goal is to verify integration, parsing, application state machines, timeouts, and error scenarios without real hardware.

- Application emulation: the terminal acts as a host system and generates queries, commands, and sequences that the device must process. The goal is to test firmware, protocol logic, fault tolerance, stability, and load response without the need for a final client application.

In both cases, it is crucial that emulation is not just “manual text sending,” but that it allows for approximation of real traffic while maintaining repeatability. In practice, there are three typical requirements that repeatedly arise in development:

- Time behavior simulation

Many devices communicate periodically (telemetry, heartbeat) or respond at defined intervals. Without a time model, applications or firmware behave differently than in reality: buffering, queue processing, timeouts, and overloads are only apparent later. The goal is to be able to generate data streams in a controlled period and test behavior at realistic and boundary intervals. - Simulation of protocol reaction logic

Many protocols are based on a request/response pattern: command, confirmation, return data, error code. The goal of emulation is to cover both normal and error branches without having to respond manually each time. It is important to be able to respond according to the recognized message pattern, not just according to one specific string. - Repeatability and reproducibility of tests

Regression tests should have the same inputs and the same order so that the results can be compared between application/firmware versions or between computers in the team. The goal is to be able to replay the same communication sequence, share it, and run it again without manual intervention. This includes the ability to pass terminal settings to other team members.

In addition to functional testing, robustness is also often addressed in practice: how applications or firmware behave when the line is overloaded, when invalid messages are received, or when non-standard sequences occur. Emulation should allow these situations to be triggered in a controlled, targeted, and repeatable manner to reveal problems such as infinite waiting, incorrect recovery, memory leaks, buffer overflows, or incorrect state switching.

This series of scenarios is based on the terminal’s ability to:

- Pack the test into a configuration that can be shared and run repeatedly,

- generate communication over time,

- play back prepared data sequences,

- automatically respond to recognized inputs.

2. Basic test topologies: physical vs. virtual cable

In practice, serial line tests are based on two topologies. The choice will significantly affect what you are able to verify and how quickly you can repeat the same scenarios.

Option A: Physical connection (real cable / USB-UART / RS-232 converter)

Schematic diagram

- Application (PC) ⇄ physical COM port ⇄ converter / cabling ⇄ device

When to use

- verification of the “entire path” including the physical layer (cabling, interference, converters, handshaking),

- integration with a prototype or finished HW,

- diagnosis of problems that do not manifest themselves on a virtual line (e.g., unstable converter power supply, incorrect RS-232 levels, incorrect signal connections).

Limitations

- Dependence on the availability of hardware and a specific converter,

- poorer reproducibility (changes in the prototype, variable behavior),

- more difficult parallelization of tests within the team (one prototype, one port).

Option B: Virtual cable (pair of connected virtual COM ports)

Schematic diagram

- Application under development (PC) ⇄ Virtual COM A

- COM Guru Terminal ⇄ Virtual COM B

- Virtual COM A ⇄ Virtual COM B (software “null-modem” connection)

This topology allows you to simulate the opposite side of the communication purely in software and isolate protocol development from hardware availability.

2.1 com0com: open source “null-modem” driver for Windows

What it does

- com0com is a kernel-mode virtual serial driver for Windows that can create pairs of interconnected virtual COM ports (the output of one is the input of the other and vice versa).

Practical test setup

- Create a pair of ports (e.g., COM10 ↔ COM11).

- Connect the application under development to COM10.

- Connect COM Guru Terminal to COM11.

- The terminal then emulates a device or application according to the selected scenario (timers, file player, autoresponse).

Note on extended topologies

- The com0com ecosystem typically also mentions a “hub” tool (hub4com), which can forward data from one port to multiple ports or combine COM and TCP, etc. (useful for more complex test routing).

Operational notes (it is advisable to state this explicitly for tests)

- The virtual cable primarily verifies the application/protocol layer. Physical layer problems (interference, RS-232 levels, incorrect wiring, converter quality) will not be apparent here.

- For virtual ports, it is advisable to have a unified installation and driver compatibility procedure within the team. For Windows, the issue of driver signing and compatibility with newer OS versions may be relevant.

2.2 Commercial solutions for virtual ports: when they make sense

Commercial tools are typically chosen when the following are important:

- easy installation on different PCs (including company policies, driver signing, no interference with security regimes),

- long-term maintenance and support,

- advanced features beyond “port pairing” (routing, port sharing, named pipes, network bridges).

Examples of commonly used solutions (by type, not as recommendations for the sole “right” choice):

- Eltima Virtual Serial Port Driver – creation of pairs of virtual ports connected by a “null-modem cable”, targeted at development/testing/debugging.

- HHD Software Virtual Serial Ports – creation of virtual ports and connection via a “software null-modem” cable, including the option of connecting to applications/virtual devices.

- FabulaTech Virtual Serial Port Control – management and creation of virtual ports, aimed at emulation and port control scenarios.

Recommended decision criteria

- If you need to quickly build a development “virtual cable” for local protocol testing, an open option such as com0com is often sufficient.

- If you need to standardize installation across the company, minimize friction with drivers, and take advantage of advanced routing or support, commercial solutions will typically reduce operating costs (especially in team and CI/test environments).

What this chapter implies for other scenarios

- Emulation of devices for application testing: typically Option B (virtual cable) + COM Guru Terminal on one side, application on the other.

- Emulation of applications for FW/device testing: either Option B (if you are testing FW via a PC application/bridge) or Option A (if you are also verifying the physical layer).

3. Use case: Emulation of devices for testing developed applications

The goal is to replace missing or unstable hardware with a deterministic counterpart that behaves like a real device from the application’s point of view. The basic topology is usually a “virtual cable”: the application runs on one virtual COM port, COM Guru Terminal on the other. This disconnects the test from the physical hardware but preserves the nature of serial communication (stream, OS-level latency, protocol-level framing).

Typical outputs that the emulation should cover

- the application correctly parses incoming data (frames/lines, checksums, separators),

- the application correctly handles the state machine (init → run → error → recovery),

- timeouts, retry logic, and error messages meet expectations,

- data processing is stable even at higher frequencies or with “dirty” input.

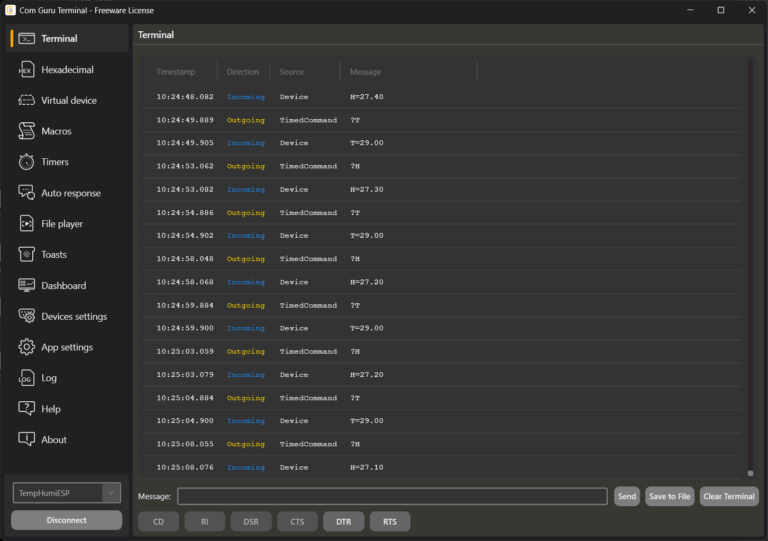

3.1 Periodic telemetry independent of commands (Timers)

The problem being tested: applications often do not just “query and wait,” but continuously receive telemetry. Without real data flow, queues, parsing over time, value aggregation, and UI/logic responses to regular updates cannot be verified.

Scenarios that make sense to emulate:

- The sensor transmits the measured value every 100–1000 ms.

- The device periodically sends its status (ready/busy, mode, temperatures, voltage).

- A heartbeat frame at a fixed interval, which the application uses to detect “device alive.”

How this is typically approached in the terminal:

- One timer for one type of message or telemetry “channel.”

- Multiple timers in parallel if the device has different periods (e.g., fast value + slow status).

- The period is chosen to match the application’s expectations (and to allow for boundary conditions: too fast sending, outages).

Examples that have proven themselves in practice:

- Heartbeat: simple frame every 1 s; the application resets the “watchdog” on each reception.

- Two periods: fast telemetry 10 Hz + diagnostics 0.5 Hz; the application must process both layers without blocking.

What to watch for when designing a test:

- Whether the application can handle reception even when sending a command at the same time (RX/TX competition).

- Whether there is a gradual slowdown (UI thread, queues, logging).

- Whether the application correctly detects “silence” (timer stopped/simulated outage).

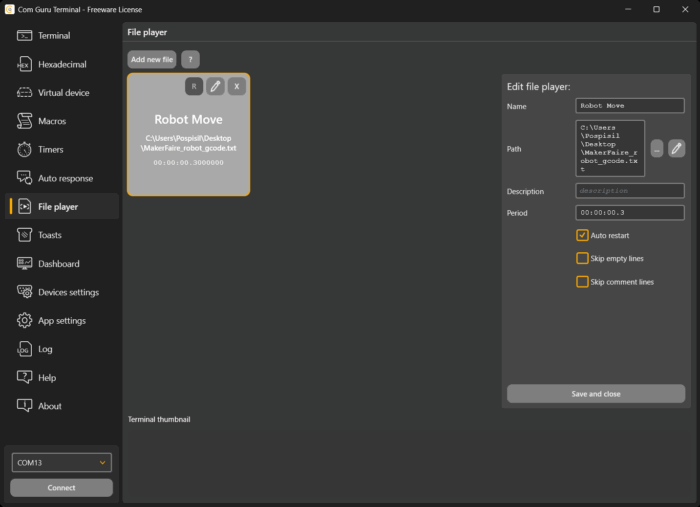

3.2 Real data flow from log (File player)

Problem tested: Manually sent messages usually do not contain variability, edge values, and “noise” from real traffic. A log from a prototype or from traffic is the fastest way to expose an application to realistic data flow.

Using the file player in device emulation mode:

- The file contains messages line by line (most often text frames or “line-based” protocols).

- The file player sends the lines sequentially at a set interval.

Scenarios you can cover:

- Regression: always the same sequence of messages; comparison of application behavior between versions.

- Parser validation: a wide range of real values, including edge cases.

- Error simulation: the log may contain incomplete/corrupted frames that the application must withstand.

Test organization: one vs. multiple file players

- One file: simple control and reproducibility, suitable for “playback scenarios.”

- Multiple file players: separation of message types (telemetry vs. alarms) and different periods. In practice, this corresponds to a device that sends different streams at different frequencies.

What to watch out for:

- If accurate time fidelity (irregular events) is important in the log, the file structure or playback method needs to be adjusted accordingly. Otherwise, the test primarily checks the robustness of the parser and the load, not the timing of specific traffic.

3.3 Responses to commands and “request/response” (Auto response + regex)

Problem being tested: a large proportion of applications are based on commanding devices. Without automatic responses, the test quickly degenerates into manual clicking and cannot be scaled or repeated.

Test principle:

- the application sends a command,

- the terminal intercepts the incoming message,

- if the message matches the rule (regex), the terminal sends a predefined response.

Typical rule categories:

- ACK/NAK model

- as soon as a syntactically valid command arrives, “ok” / confirmation is returned,

- if the format is invalid, an error is returned.

- Value queries

- a specific query (e.g., T?) returns a value in the format expected by the application.

- Status responses

- The command changes the status of the emulated device, and further responses depend on the “current mode.”

- (If the terminal maintains the status implicitly through a set of rules and running modes/timers, the correct interpretation of the status on the application side is also tested.)

Why regex:

- one rule covers a range of commands,

- syntax can be validated (i.e., “commands look correct”),

- commands from a specific group (init/config/run) can be targeted.

What to watch out for:

- the application often also expects timing (response within X ms). Auto response allows you to verify timeouts and retry logic by temporarily disabling or modifying the rule (e.g., returning an error).

3.4 Combination: telemetry + commands simultaneously (Timers + File player + Auto response)

Real devices typically send telemetry continuously and respond to commands at the same time. This combination is more important for application testing than isolated “log playback” or isolated “command response.”

Practical profile of the emulated device:

- 1–N timers for periodic data (telemetry, heartbeat),

- 0–N file players for “real world” flow or scenarios,

- set of autoresponse rules for application commands.

What you will verify:

- The application can handle parallel RX streaming and TX querying,

- the parser and state machine work even when events occur concurrently,

- logging, UI, and business logic do not reduce throughput and stability.

4. Use case: Emulation of an application for testing devices or firmware

In this scenario, the roles are reversed. The device (or its firmware) is the element being tested, and COM Guru Terminal acts as the host application: it sends queries, configuration commands, executes sequences, and responds to what the device returns. The practical goal is to have a deterministic “test client” that can be run at any time, regardless of whether the final PC application already exists.

Typical outputs that the emulation should cover

- the device receives and correctly parses commands in the expected format,

- the firmware correctly implements sequences and state transitions (init/config/run),

- responses are timely and consistent (timeouts, error codes, acknowledgements),

- the device behaves stably under load and with incorrect inputs (error handling and recovery).

4.1 Periodic queries and keep-alive (Timers)

Purpose of the test: most devices are “polled” during operation – the host periodically requests values or confirms that the connection is alive. This verifies that the firmware can handle long-term operation and that there is no degradation over time.

Typical scenarios:

- periodic query for measured value (

READ?) every N ms, - keep-alive/heartbeat (

PING) and expectation of response (PONG), - periodic status check (

STATUS?) for monitoring and diagnostics.

How to verify functionality:

- increasing the frequency of queries tests the throughput and robustness of the parser,

- omitting a query (timer stop) simulates a host failure and monitors device behavior,

- combining multiple timers simulates a real host (fast queries + slow diagnostic queries).

What is good to monitor explicitly:

- whether the device correctly distinguishes frames when queries come in quickly one after another,

- whether the device does not block RX processing when generating a response,

- whether latency does not deteriorate or internal queues do not accumulate after a long period of time.

4.2 Sequence and state machine testing (File player)

Purpose of the test: Firmware is usually not just “command → response.” It often involves initialization, configuration, mode switching, calibration, and start/stop measurement. The file player is suitable for repeatedly running the same sequence of commands and comparing results between FW versions.

Typical sequences:

- init handshake (

HELLO,ID?,CAPS?), - configuration (

SET RATE 10,SET MODE X,SAVE), - operational part (

START, continuous queries,STOP), - error branches (intentionally incorrect parameter, unexpected command sequence).

How to build it in practice:

- file for “happy path” (correct sequence),

- separate files for negative scenarios (invalid parameters, incorrect order),

- if necessary, you can have multiple file players (e.g., one for the “control” channel, another for “diagnostics”), but it is often better to stick to one deterministic scenario.

What to watch out for:

- if the device expects a certain delay between steps (e.g., time to save the configuration), the period is chosen to match the actual behavior of the host,

- for diagnostics, it is advisable to log which line of the scenario has just been executed so that errors can be easily assigned to a specific step.

4.3 Device event response (Auto response)

Purpose of the test: devices sometimes send asynchronous events (alarm, warning, ready, state change). The host must respond – confirm, switch mode, request details, or stop the process. Auto response enables simple response logic without the need to write test client software.

Typical scenarios:

- after startup, the device sends

READY→ the host sendsSTART, - the device sends

ALARM:<code>→ the host sendsSTOPandSTATUS?, - the device sends

ERR→ the host sendsRESETor switches to diagnostics.

Why regex:

- events are usually parameterized (

ALARM:123,WARN:TEMP_HIGH), - regex allows you to cover an entire class of events with a single rule and respond consistently.

What you are verifying:

- the device generates the expected events in the expected format,

- the device can handle subsequent commands even in an error state,

- the device returns to a stable state after recovery.

4.4 Combination: the host simulates “real traffic” (Timers + File player + Auto response)

The best coverage is achieved by combining:

- file player for initialization and configuration sequence,

- timers for continuous queries during operation,

- autoresponse for reactions to asynchronous device events.

This gives you a model that is close to a real application, but remains repeatable and quickly modifiable.

The result is a consistent and easily transferable procedure: the same set of steps, the same behavior, less room for manual errors.

5. Conclusion

Emulation in serial communication solves a practical problem of parallel development: one side of the interface (HW or application) is often temporarily unavailable, unfinished, or unstable. The purpose is to have a deterministic counterpart of communication that allows you to verify parsing, state machines, timeouts, retry logic, and behavior under load without waiting for the final implementation.

The basic decision is the test topology. A physical connection via a real COM port and converter is necessary to verify the physical layer and integration, but it has higher operational friction and poorer reproducibility. A virtual “cable” is suitable for development and protocol testing: a pair of interconnected ports (typically via com0com or commercial alternatives) will allow the application under development to communicate with the terminal as if it were a real device.

In device emulation mode, the terminal represents a sensor or control unit. Timers generate periodic telemetry and heartbeat frames, the file player plays real logs or prepared sequences line by line, and auto response reacts to application commands according to regex rules and returns predefined responses. By combining these mechanisms, it is possible to simulate normal operation as well as edge cases (simultaneous RX stream + TX queries, outages, incorrect inputs).

In application emulation mode, the terminal represents the host software, and the device or firmware is the tested element. Timers are used for periodic queries and keep-alive, file players for deterministic sequences (init/config/run), and auto response for reactions to asynchronous device events (ready/alarm/error). This creates a reproducible test client that can be used even before the final application is completed.

Related articles

COM Guru Terminal – new generation of serial terminal

COM Guru Terminal – simple SCADA center

COM Guru Terminal – lightweight penetration and robustness testing

COM Guru Terminal – device control and configuration